Art and Health

Art and Health

The third installment of a multi-platform series exploring the connections between art and the topics that move our world: climate, globalism, technology, science, health, law, finance, theft, international relations, destruction, religion and death.

Health may seem to be a topic nestled in place in our minds far from thoughts of art. But, in reality, the two intersect on a myriad of levels. Whether we’re tracking Monet’s ocular health through the color choices of his paintings of Giverny or using fMRI scans to measure the blood flow to varying parts of the brain when viewing art, the interplay between art and health is incredibly complex. The creation and viewing of art can impact and be impacted by one’s health. Art and Health will bring us through the well-being of artists whose work you’re familiar with already and surprise you with shocking reasons why art was once a lethal weapon.

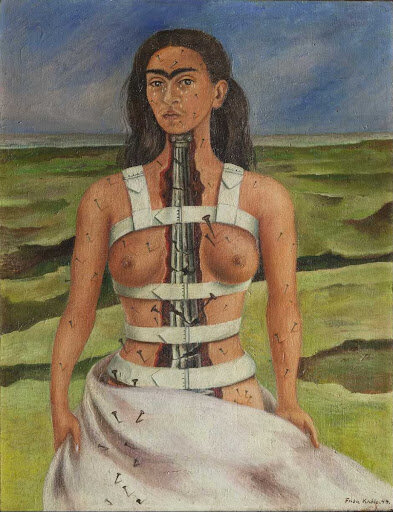

The Broken Column (La Columna Rota) by Frida Kahlo. Wikimedia Commons.

When an artist falls ill, their work is invariably reflective of their illness. Whether it reveals itself in their medium, subject, composition style or color choices, one can typically trace the impact of ill health in the artist’s creative expression. Sometimes this correlation is quite literal and reveals itself in the subject matter of self portraiture. Frida Kahlo’s, The Broken Column, explicitly addresses her recent spinal column surgery. The operation left her bedridden and tethered to a metallic corset, displayed clearly in her self portrait. Interestingly, however, her work’s interplay with health stems from a far deeper place. She had taken an early interest in medicine and had hoped to utilize her artistic ability to become a medical illustrator. When her ill health from the contraction of polio at age 8 combined with injuries from a horrific bus accident at age 18, she spent considerable time in a bedridden state and turned to painting to pass the time. To facilitate this pastime, she had a specialized easel created to allow her to paint from bed. While not being able to stand propelled her time spent painting to new heights, the opposite was true of Matisse. It was Matisse’s ill health which precluded him from standing and painting. His cancer diagnosis in 1941 resulted in a wheelchair bound lifestyle directly following his surgery. This inspired him to take up paper cuttings which could be comfortably done from his wheelchair, resulting in an entirely new era of his artistic career.

Whereas Kahlo and Matisse are examples of the artistic choices of medium and subject changing due to changes in health, one can also dive into the charting of an artist’s health decline through the analysis of more unintentional choices, especially when it comes to the relationship between color and ocular health. A prime example of this is Monet. Monet began to develop bilateral age-related cataracts (or nuclear sclerosis) in his 60s. He complained “colours no longer had the same intensity” for him, that “reds had begun to look muddy” and that his “painting was getting more and more darkened.” Throughout his time avoiding surgery, he came up with a number of fixes to counteract the illness' impact on his work. He made descriptive labels for his tubes of paint, kept a strict order of the colors on his palette and wore a huge straw hat when painting en plein air to avoid further complications from direct sunlight. Nonetheless, his brushstrokes became broader and his works were increasingly muddy in color. This can be clearly observed through two of his works, painted just one year apart between 1899 and 1900, the year his cataracts developed. When he finally acquiesced to surgery in 1923, these altered color perceptions became less prevalent and he began to destroy or retouch paintings he had made throughout his preoperative period. His style immediately reverted back to a blueish and greenish palette painted with finer brushstrokes.

The Water Lily Pond, 1899 by Claude Monet. Claude-Monet.com

The Japanese Bridge, 1900 by Claude Monet. Wikiart.com

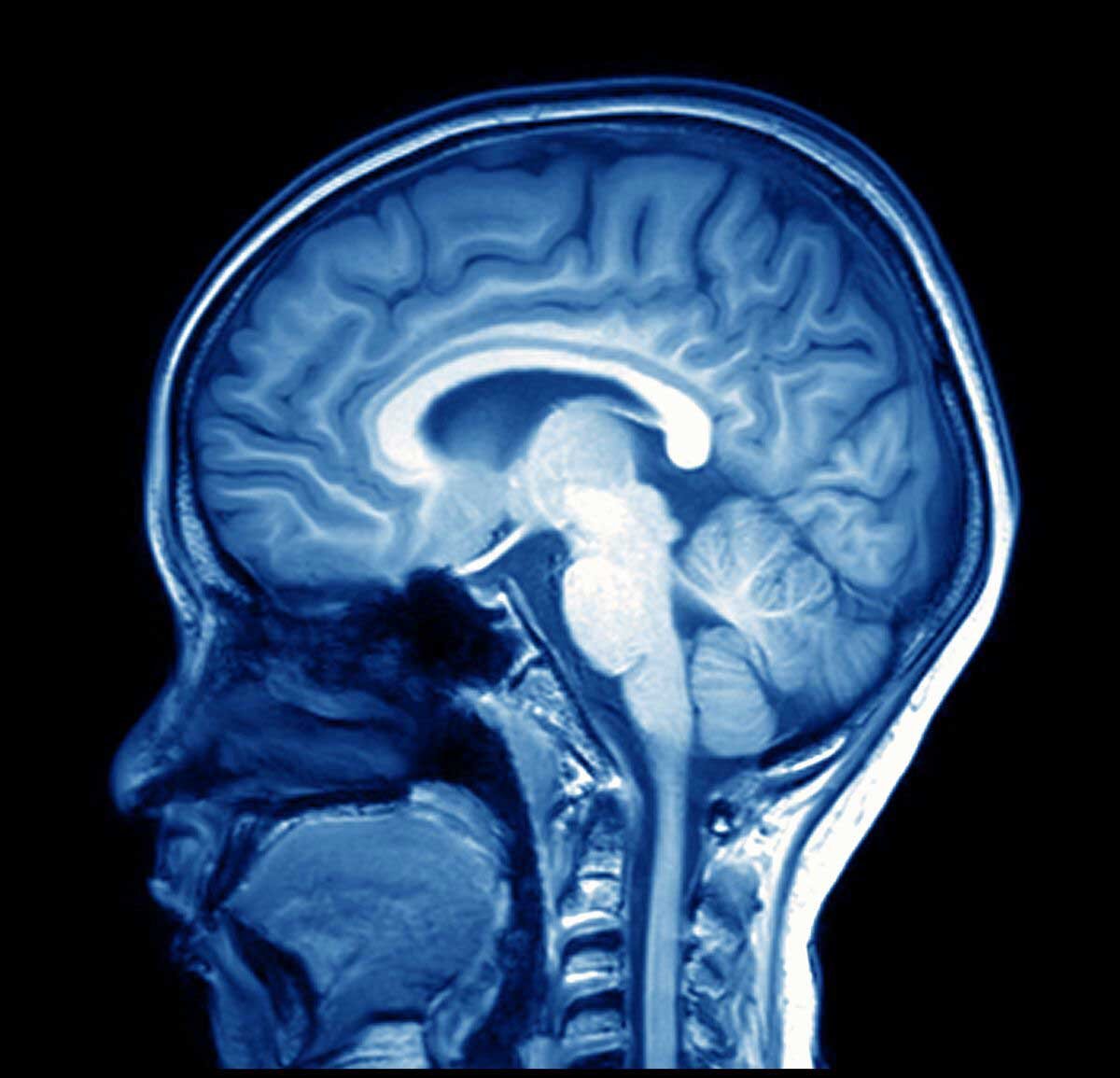

Sample brain scan from an fMRI. Wikimedia commons.

Art provides, not only a barometer of an artist's health, but the potential to improve upon it as well. Both the creation and appreciation of art have been shown to promote wellbeing and increase healthfulness. This can be charted in a number of ways including the practice of Neuroaesthetics. Neuroaesthetics is the emerging field of study charting brain activity whilst a subject views artwork. Studies showcasing the increase in blood flow to the medial orbitofrontal cortex (the portion associated with pleasure) while viewing artwork provide data indicating that the viewing of artwork can promote wellbeing. In addition to its value in preventative care and general health, the creation and viewing of art is also used as a complement to treatment through the practice of art therapy. Art therapy has been used to improve cognitive and sensorimotor functions, foster self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivate emotional resilience, promote insight, enhance social skills, reduce and resolve conflicts and distress, and advance societal change. A comprehensive study was published by the World Health Organization (WHO), detailing the connection between culture and health through academic research. It brought together 900 different publications over a 19-year span in a historic 146-page report. Multiple studies showed that the utilization of art therapy in cancer treatments significantly improved the emotional state and perceived symptoms of the patients, providing a powerful tool for the management of pain. Beyond preventative care and pain management, art can also be a powerful tool in the management of symptoms present in dementia patients. A study found that the viewing of visual arts led to longer time of sustained attention than did many other activities, providing much needed stimulation of the brain for patients suffering from the disease.

Art can promote well-being and healing but, in certain instances, it can prove incredibly detrimental to health as well. For centuries, artists concocted their own materials. This included the creation of potter’s glaze, the mixing of paints and the stretching of canvases. Paint colors were made through the combination of pigments and binders. The pigments were often ground minerals and metals. The paints created often contained substances incredibly harmful to one’s health and the physical impact could either be on the creator of the work or the viewer, depending on the substance’s chemical makeup. For instance, there was a vivid green color developed by a Swiss chemist in the early 1800s called Scheele's Green, also known as Schloss Green. It was created through the use of an arsenic compound which rendered it lethal as it aged. As such, when works created using Scheele's Green aged, they released arsenic into the air and transformed into silent lethal weapons. Once the connection was made between the secret toxicity of the green paint and its adverse health effects, it was swiftly passed over in favor of other pigments. That, however, was not always the case.

Durable white paint is a valuable tool in an artist’s arsenal due to its ability to create chiaroscuro in landscape, portrait and still life. It just so happens that one of the most durable pigments in the creation of white paint is comprised of Lead. Although the Dutch knew about the toxicity of lead as far back as the 1700’s, Dutch painters including Johannes Vermeer himself utilized the lead based paint for its incomparable brightness. Whereas some artists knowingly used lead based white, others unknowingly used cadmium red to create deep jewel tones and rich warm colors like orange and yellow. The color was discovered by a German chemist in 1817 and artists quickly fell in love with the saturation, prizing it as the best red hue money could buy. However, more recently health officials have gotten involved, as the mere washing of paint brushes that had been used to paint cadmium derived colors was said to have polluted the water supply in Sweden. A fiercely contested battle ensued within the EU about the possible ban of the pigment but ultimately the artists prevailed. The sale and disposal of cadmium are now heavily regulated but it is still technically legal to use. It is not only paint which can prove detrimental to health, other artists’ materials can be hazardous as well. Uranium based glazes dating back to the birth of Christ have covered pieces of pottery and up until the 1970’s pottery was being dyed with uranium yellow hues. Although the practice is now banned, the artists working with these uranium glazes were unknowingly exposing themselves to dangerous levels of radiation.

Johannes Vermeer, The Procuress (1656). Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Whether it's the reflection of an artist’s change in health in their art, the creation or appreciation of art being used to manage the health of a patient or the art itself slowly poisoning the artist or viewer- art and health intersect in a plethora of ways. These disparate seeming topics can be intrinsically linked and hold surprising connections for both the benefit and detriment of one’s health. Subscribe for next week as Art and dives into the world of Law!

Subscribe to Art and

Sign up and get the next installment sent to your email.

Sources

Art Therapy | Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/therapy-types/art-therapy. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

“Artists ‘Have Structurally Different Brains.’” BBC News, 17 Apr. 2014. www.bbc.com, https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-26925271.

“Brain Scans Reveal the Power of Art.” The Telegraph, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-news/8500012/Brain-scans-reveal-the-power-of-art.html. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

Carelli, Francesco. “‘Painting with Scissors’: Matisse and Creativity in Illness.” London Journal of Primary Care, vol. 6, no. 4, 2014, p. 93.

Ferreira, Rute. “Artists Who Suffered Mental Illness And How It Affected Their Art | DailyArt.” DailyArtMagazine.Com - Art History Stories, 6 Oct. 2020, https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/artists-who-suffered-mental-illness/.

Frida Kahlo. https://www.healing-power-of-art.org/frida-kahlo-created-art-that-transcended-her-suffering/. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

Gruener, Anna. “The Effect of Cataracts and Cataract Surgery on Claude Monet.” The British Journal of General Practice, vol. 65, no. 634, May 2015, pp. 254–55. PubMed Central, doi:10.3399/bjgp15X684949.

Guzman, Alissa. “The UN’s World Health Organization Says Art Is a Powerful Prescription.” Hyperallergic, 22 Nov. 2019, https://hyperallergic.com/528351/world-health-organization-art-medicine/.

How a Horrific Bus Accident Changed Frida Kahlo’s Life - Biography. https://www.biography.com/news/frida-kahlo-bus-accident. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

Marmor, Michael F. “Ophthalmology and Art: Simulation of Monet’s Cataracts and Degas’ Retinal Disease.” Archives of Ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill.: 1960), vol. 124, no. 12, Dec. 2006, pp. 1764–69. PubMed, doi:10.1001/archopht.124.12.1764.

Regev, Dafna, and Liat Cohen-Yatziv. “Effectiveness of Art Therapy With Adult Clients in 2018—What Progress Has Been Made?” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 9, Aug. 2018. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01531.

Tate. “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs – Exhibition at Tate Modern.” Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/henri-matisse-cut-outs. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

The Toxic Histories of Five Famous Pigments. https://info.noahtech.com/blog/the-toxic-histories-of-five-famous-pigments. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review (2019). https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/what-is-the-evidence-on-the-role-of-the-arts-in-improving-health-and-well-being-a-scoping-review-2019. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.