Meaning, Made

Crisis and Hope in Black America

‘Blackness’ is many things, and has been since the first enslaved Africans were brought to the shores of North America. But one thing has tied every generation together since then: the need to be one’s one agent of creation and forge a meaningful life in a society especially made to fail them. This unique tint on the existential window is captured in writing by authors like Toni Morrison and Richard Wright, but what do we see when we apply this lens to visual art and artifact?

The images in this digital exhibition were curated within the restrictions of the public domain and the creative commons. These constraints present a challenge — we cannot seek the obvious (and many!) artistic statements made in the most recent decades. Instead, as you look upon these works, think about what Blackness has meant over time, both to the subjects and the artists. As we look at Blackness in a non-Black land, specifically the United States (and, briefly, in Europe) ask yourself what it means to create your own meaning and define your own life— to dare to be present, to thrive, to rage, and to hope in a society that would rather see you dead?

Terracotta column-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water) [Obverse, artist painting a statue of Herakles]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Terracotta column-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water) [Obverse, artist painting a statue of Herakles]

(ca. 360–350 B.C.)

When ancient Greeks drank wine they diluted it with water, often a vessel called a krater. The obverse of this particular krater centers an artist applying pigment to a statue — itself a relatively rare depiction. He operates under the guise of Zeus and Nike; to his left enters the hero Herakles, the subject of the artist’s work. But to the left of the partially pigmented sculpture, we see a fully pigmented human — an African boy, tending the brazier. To ancient Greeks, all dark-skinned African people were known as “Ethiopians” a designation that itself confers a semi-mythical status on dark-skinned individuals — “Ethiopia” itself was believed to be a mythical land. While we don’t know what prejudices, if any, existed between both groups, thinking about the African in Greece makes us consider the task of living a fully personal human life under the gazing, exoticizing eyes of a society’s majority.

Metropolitan Museum Purchase, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan and Bequest of Helena W. Charlton, by exchange, Gwynne Andrews, Marquand, Rogers, Victor Wilbour Memorial, and The Alfred N. Punnett Endowment Funds, and funds given or bequeathed by friends of the Museum, 1978. (Public Domain)

Pilate Washing His Hands (Mattia Preti)

(1663)

According to the New Testament, Pontius Pilate, the Roman Governor who presided over the trial of Jesus, washed his hands of the matter of the prisoner’s condemnation or release — an act that Preti depicts in this 17th-century painting. But for us, it’s neither Pilate or the barely visible Jesus that is of concern here. Instead, it’s the Governor’s young, bejeweled African attendant. By thrusting this melanated character into the center of his work, Preti is (perhaps inadvertently) providing the viewer with a window into the increasingly violent relationship between Europe and Africa. The Met’s label points out that at the time, Preti was working in Malta, and the presence of a dark-skinned figure was indicative of the island’s “increasingly multiracial population,” a consequence of their involvement in the slave trade. As Preti inserts Pilate’s black attendant into a moment of literary import, our mind turns towards the looted individuals who were thrust into a foreign land and — retroactively — a crucial narrative in the annals of Afro-European relations.

Metropolitan Museum, purchase, Friends of the American Wing Fund and Aliva Baker Gift, in honor of Derrick Beard, 2019. (Public Domain)

Face Vessel (Unidentified Edgefield District Potter)

(19th Century)

The face vessel remains an enigma of folk art; their existence is clouded in unknowns. While these jugs are surely functional as vessels for water, scholars have wrestled with the question of why they are so personalized. Was it for spiritual practice? Or a connection to West African artistic practices? Or, as the Smithsonian wonders, a “complex response of people attempting to live and maintain their personal identities under harsh conditions”? A consequence of the attempted erasure of the humanity of these creators is that we may never know. Perhaps divorced from its original function, the face on this jug looks at us, eyes wide and teeth bared, mocking a uniquely American arrogance. Its dark skin is imbued with the secrets of a people expressing their creativity while making a bid to stay alive.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., 1983.95.178 (Public Domain)

Hagar (Edmonia Lewis)

(1875)

Quranic and Biblical narratives exist of Hagar/Hajar and Abraham/Ibrahim, with slight variances in the relationships between the central characters. In essence, the couple conceived a son, Ishmael/Isamail. This was much to the chagrin of Sarah, who demanded they be sent away. The new father acquiesced to this wish, leading them to the barren lands of Mecca. But Hagar’s faith, despite this abandonment in the desert, assured providential guardianship and the flourishing of who would become equated with Arab people. Here, African-American and Ojibwe sculptor Edmonia Lewis depicts the matriarch with hands clasped and upward gaze, pleading with the divine. Included also is evidence of her dire situation, an empty pitcher of water. Despite thirsting in the desert, she is bold to hope — and hold her god to account — to create something from nothing.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Mr. and Mrs. William Preston Harrison Collection (Public Domain)

Daniel in the Lions' Den (Henry Ossawa Tanner)

1907-1918

Many of Tanner’s paintings deal with Biblical subjects, and it’s hopefully not lost on viewers that these religious figures — whether persevering in the face of oppression or the unjust victims of state violence — may have provided some kind of inspiration to Black Americans. Here, we see a representation of Daniel, condemned to execution via the mouths of lions. But, in a twist ending, the beasts do not attack the innocent man, and he lasts the night definitively uneaten. Tanner chooses to depict an expectedly frightening scene by evading fear and embracing cool colors and textured strokes evocative of an impressionist idiom.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Beverly J. Blackwood in memory of Charles J. Blackwood, Sr. (Public Domain)

Framed panoramic photograph of 183rd Brigade of the 92d Infantry Division (Duce & McClymonds)

The 92nd Infantry Division, (also known as the Buffalo Soldiers due to the unit’s insignia, itself derived from a 19th-century nickname for black cavalry) saw its first combat action during the final year of World War I. This photo was captured during that year, and this panorama dispels any doubts one might have about the fitness of Black soldiers in the armed forces. Looking here, we remember that a great deal of these infantrymen chose this fight, an entrance onto a global stage, to set an example for American patriotism and excellence abroad. But the collective hope we feel with the faceless in this photograph is tempered by hindsight that comes with the knowledge of the violence and contempt that awaits them upon their return, prompting the choice for yet another fight and making of meaning.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of New York City W. P. A., 1943 (Public Domain)

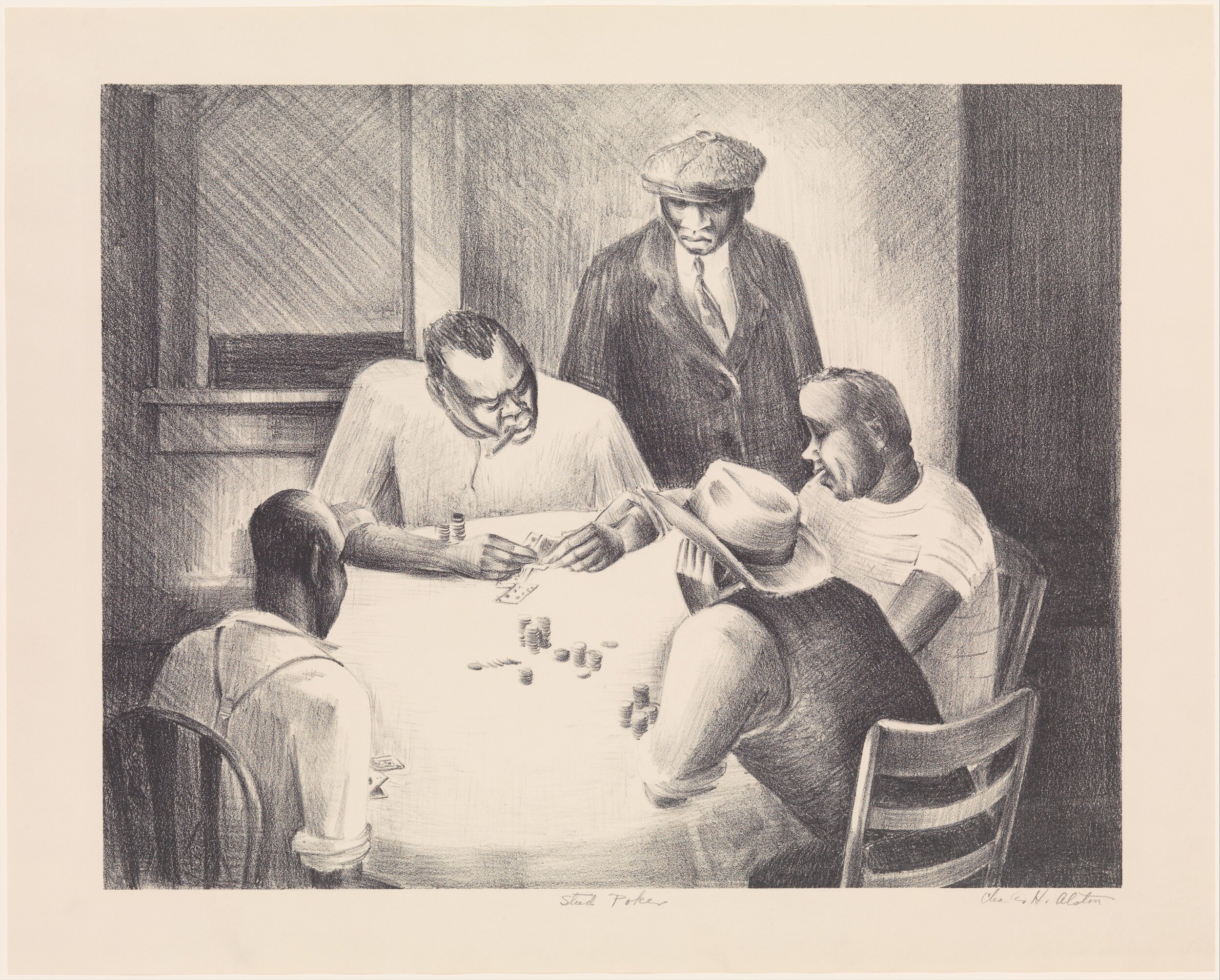

Stud Poker (Charles Henry Alston)

Alston’s life was its own vision of America — Born in Charlotte, raised in New York, educated at an elite college, and founder of 306, an intellectual creative nexus during the Harlem Renaissance. He was also a supervisor the depression-era WPA’s Federal Arts Project, and here we see a product of that funding: a scene featuring four men playing a game of stud poker, complete with a curious spectator. This is an example of Alston’s mission to capture the life of black America, divorced from the curious white gaze or the expected narrative of righteous struggle. Here we see a snapshot of a society with its own highs, lows, thrills, and mundanities. In it’s won way, this otherwise uneventful game night is a triumph in and of itself — the act of simply being.

Who Likes War? or Justice at Wartime (Alston). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division. The New York Public Library.

Who Likes War? or Justice at Wartime (Alston)

Ca. 1938

This Alston, decidedly more metaphorical in nature, was created during the early years of a global war. We see justice personified, emaciated and burdened by her scales, themselves laden with weapons. She is standing alone and barefoot in a graveyard, cradling a cannonball, making for a sight most macabre. While memory likes to remember an America united against the specter of a Nazi horde, University of Alabama professor Stacy I. Morgan points out that the Left was generally antiwar in the early years of the conflict. Such a sentiment is difficult to uncouple from the knowledge that American intervention abroad would have been considered rank with hypocrisy to those living under the weight of oppression from their own government.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. (Public Domain)

Gladys Bentley: America's Greatest Sepia Player -- The Brown Bomber of Sophisticated Songs (Unidentified)

(1946-1949)

The daughter of Trinidadian immigrants, Gladys Bentley was a leading singer and pianist who achieved the height of her fame during the Harlem Renaissance. Here, Bentley is dressed finely in a white tuxedo complete with coattails, cane and top hat, a wry grin on her face. She was openly lesbian, and unabashedly herself when it came to matters of style — both in music and fashion. During the fearmongering McCarthy years, she assumed a more traditional gender role and expression, but she should be considered an example of someone who lived a fearless artistic life.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of James F. Dicke, II. (No Known Copyright Restrictions)

Building brick from the White House

Removed 1950

During the 2016 Democratic National Convention, First Lady Michelle Obama delivered a speech that included an assertion that deeply upset many a listening American: “I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.” Let this brick remind us that she was not wrong: the structure that houses the nation’s most powerful executive came courtesy of those who have for so long been kept out of it.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. (Public Domain)

Black Power (Alfredo Rostgaard)

(1968)

This print, published by the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL) in 1968, features the declaration of “Black Power” printed inside the maw of a red-eyed black panther. With the reminder of "Retaliation to Crime: Revolutionary Violence" written in English, French, Spanish and Arabic, the viewer is reminded of the power of solidarity and the far-reaching nature of decolonization. The Black Panther Party, in particular, is a reminder of the possibilities of “doing it yourself.” Rather than wait for aid and justice the party sought it themselves, establishing community patrols of police, the Free Breakfast For Children program, and an articulated 10-point plan that outlined what true liberation actually looked like.

![Terracotta column-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water) [Obverse, artist painting a statue of Herakles]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7bd7d5c2ee4e4a33137a1a/1602657321723-VQ5B8LUACKNKRUNPJF3Z/DT282.jpg)